FREE Short Story: The Seamstress

For your FREE short story, type your email address below.

You'll get the short story, plus fun facts about the Wild West, and news about upcoming stories.

For your FREE short story, type your email address below.

You'll get the short story, plus fun facts about the Wild West, and news about upcoming stories.

This year, 2024, marks several auspicious events in the history of relations between the United States government and Native Americans. You can decide if it is an anniversary to celebrate or not.

Two hundred years ago, on March 11, 1824, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun administratively established the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) within his department. It is interesting to note that the United States deemed it necessary to conduct relations with Indian Nations through the War Department at that time. In 1849, the BIA was transferred to the newly created Interior Department. In the years that followed, the Bureau was known variously as the Indian office, the Indian bureau, the Indian department, and the Indian service. The name “Bureau of Indian Affairs” was formally adopted by the Interior Department on September 17, 1947.

administratively established the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) within his department. It is interesting to note that the United States deemed it necessary to conduct relations with Indian Nations through the War Department at that time. In 1849, the BIA was transferred to the newly created Interior Department. In the years that followed, the Bureau was known variously as the Indian office, the Indian bureau, the Indian department, and the Indian service. The name “Bureau of Indian Affairs” was formally adopted by the Interior Department on September 17, 1947.

Since 1824 there have been 45 Commissioners of Indian Affairs of which six have been American Indian or Alaska Native: Ely S. Parker, Seneca (1869-1871); Robert L. Bennett, Oneida (1966-1969); Louis R. Bruce, Mohawk-Oglala Sioux (1969-1973); Morris Thompson, Athabascan (1973-1976); Benjamin Reifel, Sioux (1976-1977); and William E. Hallett, Red Lake Chippewa (1979-1981).

The BIA was responsible for the treaty agreements negotiated by the United States and tribes in the late 18th and 19th centuries, most of which were broken and rewritten by the US government. The most notorious result of the broken promises was the Trail of Tears, the forcible removal of thousands of Natives in the 1830s from the eastern states to ‘Indian Territory’, as Oklahoma was then known. Up to a quarter of those undertaking the journey, on foot and in horrific conditions, died, including the wife of the Cherokee Chief John Ross, who had tried to negotiate for better treatment of his people.

Then came the General Allotment Act of 1887, which opened tribal lands west of the Mississippi to non-Indian settlers. This was exploited by the boomers, who petitioned the government to open up ‘Indian Territory’ for non-Indian settlers as well. Soon, a number of ‘Land Runs’ were organized for Indian Territory, allowing anyone to register a claim for a ‘quarter section’ (160 acres), provided he/she got there first on the appointed day.

My own great-grandparents took part in the biggest Land Run, September 16, 1893, in which over 100,000 hopefuls ran for 40,000 quarter sections in what was known as the Cherokee Outlet or Cherokee Strip, land that had previously been granted to the Cherokee ‘in perpetuity’ by the BIA. My great-grandparents, who were most likely unaware of this, were successful in claiming a parcel of land in northwest Oklahoma, where they farmed for fifteen years. I took their story and imagined what it must have been like to homestead in territory taken from the Cherokee in my novel The Cherry Stone.

My own great-grandparents took part in the biggest Land Run, September 16, 1893, in which over 100,000 hopefuls ran for 40,000 quarter sections in what was known as the Cherokee Outlet or Cherokee Strip, land that had previously been granted to the Cherokee ‘in perpetuity’ by the BIA. My great-grandparents, who were most likely unaware of this, were successful in claiming a parcel of land in northwest Oklahoma, where they farmed for fifteen years. I took their story and imagined what it must have been like to homestead in territory taken from the Cherokee in my novel The Cherry Stone.

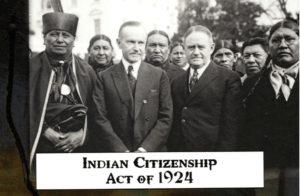

One hundred years ago, the tide shifted, and the BIA enacted the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 when American Indians and Alaska Natives were granted U.S. citizenship and the right to vote. This seems to be a step in the right direction, conferring ‘equal rights’ to Native Americans. However, it comes immediately after the movement to deny Natives the right to self-determination. In 1906, the Cherokee Nation was officially dissolved, and the tribe was no longer recognized by the United States as a law-giving or law-enforcing body. Other tribes were similarly denied such rights.

1924 when American Indians and Alaska Natives were granted U.S. citizenship and the right to vote. This seems to be a step in the right direction, conferring ‘equal rights’ to Native Americans. However, it comes immediately after the movement to deny Natives the right to self-determination. In 1906, the Cherokee Nation was officially dissolved, and the tribe was no longer recognized by the United States as a law-giving or law-enforcing body. Other tribes were similarly denied such rights.

Activism in the 1960s and 1970s saw the takeover of the BIA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., and led to the passage of landmark legislation such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the Tribal Self-Governance Act of 1994, which have fundamentally changed how the BIA and the tribes conduct business with each other. Now it is possible for those with a heritage rooted in Native tribes to claim citizenship to that particular nation, while also holding U.S. citizenship. The validity and value of both cultures is recognized.

I hope that, during this year of Anniversaries, respect for native American cultures continues to grow. It is important that we are aware of the history, and that the history is told accurately, not just from one viewpoint but representing the different perspectives involved.

So, should we celebrate this anniversary year? You decide, but by all means celebrate the diversity of cultures the anniversaries represent.

The Cherry Stone: A Family’s Struggle to Homestead in Cherokee Territory

The Cherry Stone: A Family’s Struggle to Homestead in Cherokee TerritoryHomesteading isn’t easy. Especially on someone else’s land.

Living with her in-laws is stifling. Paulina longs for a home of her own. Her husband needs land to farm and jumps at the chance of a free homestead in Oklahoma. It’s the craziest lottery in history – the great Land Rush of 1893. But how secure will Paulina and Gerhard’s young family be on territory stolen from the Cherokee?

Tsali seeks security for his family too, but the white men are trampling over his Cherokee heritage. Will he conform to the settlers’ way of life, or be drowned by it?

As drought bites and cultures collide, Gerhard is forced to leave the homestead in search of work. Paulina encounters the Cherokee family living nearby, and is grateful for Tsali’s help during her husband’s absence. But their friendship threatens to tear her family and close-knit Mennonite community apart.

“A charming tale of bravery and hope.”

C. Russell, Sidmouth, U.K.

Follow this link for the novel: https://mybook.to/TheCherryStone

Thanks to www.bia.gov for information in this article.